Remembrance of what I have lived in my home are like drops of water refreshing my daily life. The celebration of the “Day of the Dead” or “All saints” as my grandparents were calling it, was a celebration-party we were waiting for with great joy. Since January or February we could hear our grandfather or father saying «that pig» is for the “deceased” and we were fattening it during the whole year until October 31st when it was slaughtered and this ritual was an opportunity to enjoy, meet and sharing together. With the meat of the pig we were preparing the “tamales” for the “altar” or to take them to the cemetery.

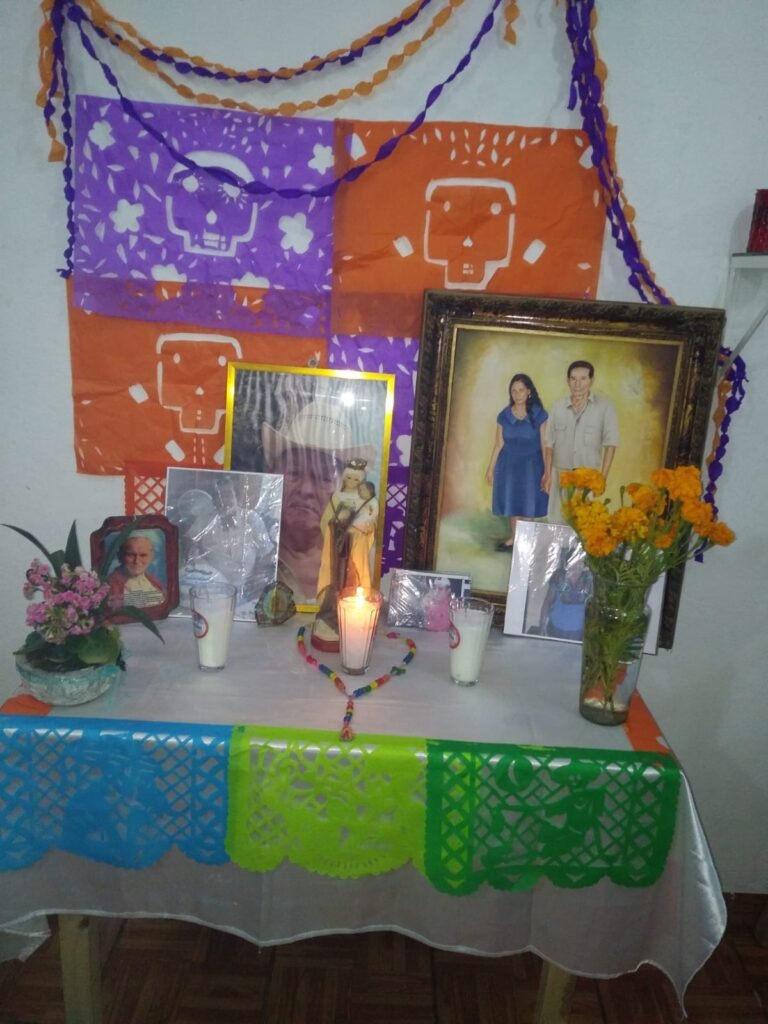

In Tabasco, my homeland, located in the south of Mexico, we make sweets of papaya and pozol, a corn drink with cocoa and we give them to the families and closest neighbors and, of course, we offered on the altar. I remember that we, the little ones, had to clean the banana leaves needed for the tamales and to prepare the vases with glass jars; the flowers were wildflowers and from Mom’s garden. We were making the cempasúchil flowers with crepe paper and my uncles chopped with skull drawings, the tissue paper we were using as decoration. In my house the “offering” or the altar was presided by a big image of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and, beside it, a wooden image of Christ and a photo of our deceased beloved ones. My grandfather used to say “your grandmother liked this” and that was what we were putting on the altar of the dead, “her favorite food”.

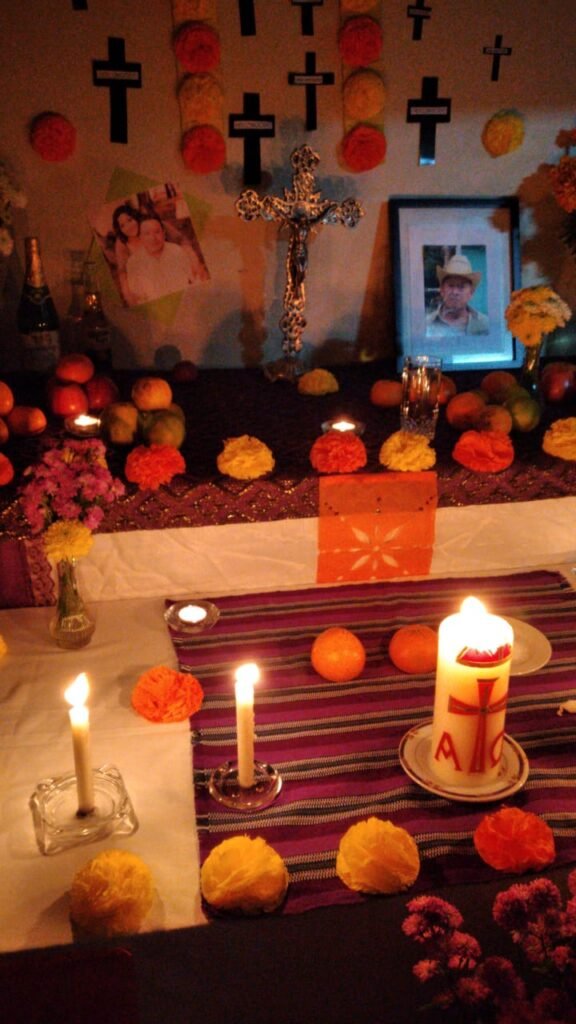

In addition to the food that we were putting salt, a glass of water and incense with copal and, of course, the candles. All that was taking place between October 31st and November 1st because, according to our customs, it was believed that the deceased began to arrive since 3:00 o’clock in the afternoon, depending on the death they had suffered.

In our house, on the first day, we were waiting until 10:00 o’clock at night and, at that time, we were remembering those who had died. My grandfather used to talk about people who had lived before us and about what liked and we were evoking and all the names of known people up to the great-great-grandparents. At that time, we were lighting the candles, one for each deceased and one for the lonely soul, Mom was leading the rosary and we all were praying and singing: «Come out, come out, come out, souls of sorrow; may the holy rosary break its chains …». At the end of the rosary, aware that they were already with us, we were eating tamales with coffee and brandy.

On November 2nd, we all were going to the cemetery to the tomb of my father’s mother and we were visiting the tombs of my mother’s parents. There we were praying the rosary and if we were meeting other relatives we shared with them the tamales. This day we were not working because tradition says that if you work, the dead get scared. All the month of November we used to pray the rosary while burning candles and my mother was saying that we could not go to bed after 12:0 at night because the “souls” would take us away … And that’s how we grew up.

At present, in my family home, on the “altar of the dead”, there are more photos but the tradition is still the same but with a more religious meaning: our grateful remembrance of our loved ones fills our hearts with love for them and it is impossible to prevent that a tear flow down on our cheeks.

But I like also to tell you that the origin of this Mexican tradition dates back to pre-Hispanic times. This festival is one of the most important feast day of the Mexican people: t is a very special day celebrated in a very particular way and considered the annual visit of the spirits of our deceased loved ones.

According to historians, the pre-Hispanic tradition says that the “mexicas” were celebrating their dead, in several periods of the year but the most important ones were at the end of the harvest, in the month of August and it was believed that, deceased people were going to a place of abandonment and sadness where they were losing memory and never eating anything; only in the month of August, the month of harvests, in the first part of the month, children were allowed to come and eat with their relatives and, in the second part of the month, it was the moment of the adults.

Aztec society believed that life continued even in the after-life and that is why it considered the existence of four «destinations» for people, according to how they died. The most common was “El Mictlán”, the place where most of the dead were going.

With the arrival of the Spaniards, the Day of the Dead did not completely disappear, as well as other Mexican religious festivals. The evangelizers discovered that there was a coincidence of dates between the pre-Hispanic celebration of the Dead and All Saints’ Day, dedicated to the memory of the saints who died in the name of Christ.

Let us remember that All Saints feast began in Europe in the 13th century and on this day the Catholic martyrs’ relics were exhibited to be worshiped by the people. There was also synchronicity with the celebration of the departed faithful, held just one day after All Saints. It was in the 14th century that the Catholic hierarchy included this festival in its calendar and in Mexico they took advantage of it. That is how the Day of the Dead was reduced to just two days, November the 1st and 2nd.

The pre-Hispanic customs still existing at the arrival of the Europeans, consisted in cremating the dead or burying them at home; these customs were cancelled and they began to deposit the corpses in the churches (the rich inside and the poor in the atrium). Some other customs were adopted, such as eating bone-shaped desserts and the very popular “bread of the dead” and “sugar skulls”.

It began also the custom of preparing an altar with candles or tapers where the relatives were praying for the soul of the deceased to help him to reach heaven. In the same way, it became traditional the visit to cemeteries that were created towards the end of the 18th century that, to prevent diseases, were built on the outskirts of the cities.

Currently this tradition, as mentioned, is one of the most important of the Mexican people and it has a spiritual sense, that has grown more and more taking into consideration the three states of the Church in which we live in communion and giving to the same altar of the dead or offering a Christian meaning. We, the Catholics, make an offering and pay homage to our deceased brothers and their families using the most common elements. The water, reminding us baptism, the candles, sign of the risen Christ, the portrait of the deceased ones, expressing that they continue to live in our mind and heart, the bread of the dead, marigold flowers, sugar and chocolate skulls, incense, perforated paper, and the food that they enjoyed during their life are part of our celebration without falling into syncretism. We do everything as a reminder of those who have already departed from us, but the peculiar thing is that everything we use in the offering has taken on a Christian meaning.

Sr. MARCELA CUNDAFÉ CRUZ, TC